Blog by: Shashwat Gupta & Himani Gupta (PGP 2018-20)

Introduction

The past few months have been marred with growing tighter money conditions and fears of contagion following IL&FS debt crisis, and has put a dent on the credit landscape in the world’s fastest growing economy.

The headlines on ‘Corporate loan growth revival’, ‘credit flow to industry, to NBFCs, priority sector, and the feuds between Government and RBI asks out more questions than it answers. So what exactly are these lending vehicles? How does bank divide loans among these sectors, how have they fared and why is Government and RBI at odds with one another? Let’s venture into the credit economy of India.

Gross Bank Credit

Bank Credit is the total borrowing capacity bank provides to its borrowers. Gross Bank Credit is the aggregate amount of credit made available to individuals or businesses from India’s various scheduled commercial banks, fueling production and consumption, and in effect the overall economy.

Gross Bank Credit, as on Oct 26, 2018 stands at Rs. 80.57 lakh crore, about 45% of the country’s GDP! Monumental as it sounds, it had grown a bit sluggish at ~6% from Oct ‘16 to Oct’17 but returned to its double-digit annual growth this year at near 13%.

*in billion Rs.

Source: RBI

Let’s break open this shell. What all does it comprise? The following image gives a pictorial view.

Food Credit

Food credit is the loan provided to the Food Corporation of India (FCI) and state government agencies to procure food grains from farmers, implementing the food policy of India. FCI does the same through supporting operations, procurement, storage, preservation, movement and distribution of food grains throughout the nation through the public distribution service (PDS) The loans are repaid after the central government releases the food subsidy, and is hence perceived to be a zero risk lending by banks.

The quantum of food credit is determined by external factors like the nature of monsoons during the year, the borrowing made, size of the market surplus, apart from the government’s food grains procurement plans.

Besides availing short term loans that are unsecured, FCI avails of a cash credit limit (CCL), fixed by the RBI, that it borrows from banks through a consortium led by the State Bank of India. These limits are fixed against the value of food grain stocks held with the corporation.

It was in 2016, when RBI suspected that the stock of foodgrains against which the loans are extended were not adequate to cover the value of the loan. It had then asked the banks to treat these ‘safe loans’ as potential Non Performing Loans and to set aside some funds. This had then come as a rude shock to the banks who were already distressed with the growing corporates NPAs.

As on Oct ‘18, Food credit is at Rs. 0.55 lakh crores or less than 1% of the total Gross Bank Credit provided.

Non Food Bank Credit (NFBC)

Anything apart from food credit comes under the gambit of Non Food Bank Credit. As seen above, more than 99% of the Gross Bank Credit goes to NFBC. It amounted to Rs. 80.02 lakh crores, growing at a strong rate of 13.4% y-o-y as on Oct ‘18.

The following image shows the broad breakdown of NFBC and its recent percentage share as per credit quantum.

Credit to Agriculture & Allied Activities

Agriculture and allied activities constitute the single largest contributor to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), accounting for almost 33% of the total. They are vital to the national well-being, providing the basic needs of the society and the raw materials for some of the important segments of Indian industry. They also provide livelihood for almost two thirds of the workforce.

Over the last four decades, agriculture has made important strides in our country, and the importance of credit has grown multifold. At Rs. 10.6 lakh crores, the credit to this sector has grown at 8% since Oct ‘17.

Credit to Industry

Credit to Industry comprises of the major chunk (~34%) of Non Food Bank Credit and is pegged at Rs. ~27 lakh crores, growing at a paltry rate of 3.7% annually this Oct ‘17. Credit to the industry has been slowing down since Sept ‘16, contracting by 1.7% for the first time in Oct ‘16. The fall can be partly attributed to the twin-balance sheet problem (highly indebted companies and banking system plagued with rising NPAs) and partly due to a slowdown in credit demand post demonetization.

The credit can be subdivided as per business size as shown in the image below.

It can also be divided on the industry the credit is allocated, as shown in the table below.

| Industry | % Share of credit to industry | % Share of new credit to industry (Oct ’17-18) |

| Infrastructure | 35% | 73% |

| Basic Metal & Metal Product | 14% | -38% |

| Textiles | 7% | 3% |

| Other Industries | 7% | -3% |

| Chemicals & Chemical Products | 6% | 17% |

| All Engineering | 6% | 7% |

| Food Processing | 5% | 6% |

| Construction | 3% | 8% |

| Vehicles, Vehicle Parts & Transport Equipment | 3% | 8% |

| Gems & Jewellery | 3% | 0% |

| Cement & Cement Products | 2% | -2% |

| Petroleum, Coal Products & Nuclear Fuels | 2% | 4% |

| Rubber, Plastic & their Products | 2% | 4% |

| Mining & Quarrying (incl. Coal) | 2% | 11% |

| Paper & Paper Products | 1% | -1% |

| Beverage & Tobacco | 1% | -2% |

| Wood & Wood Products | 0% | 1% |

| Leather & Leather Products | 0% | 0% |

| Glass & Glassware | 0% | 2% |

The above table also shows the industries where the new credit allocation in ‘17 -’18 is accelerated as compared to its credit share in ‘18.

As seen above, credit to major sub-sectors such as infrastructure, chemicals and food processing accelerated in Oct’18, while the credit to cement and products as well as to basic metals saw a contraction. With the non-banking financial companies (NBFCs), a major source of financing for MSMEs, denting the sector with stressed loans, the increase in the flow of funds to industry can be viewed as a relief for Micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs).

Also, the proposed loan restructuring mechanism by RBI with loans upto Rs. 25 crore for MSMEs will be a positive for this sector. The initiative by Modi government to introduce a portal for sanctioning loans to an MSME’s within 59 minutes may seem like a good initiative, but the availability of credit from formal sources has remained a problem for the sector.

Credit to Services

Credit to Services sector accounts to 28% in Oct ‘18, but hogged the lion’s share (~50%) of the new loans in Oct ‘17 – Oct ‘18. The quantum is fueled by major credit increase to NBFCs. Banks are increasingly using NBFCs to do their lending for them. The increase in credit has come at a time when NBFCs are finding it difficult to secure short term funding from the money markets and are increasingly looking up to banks for their liabilities. Total bank credit to NBFCs soared by over Rs 2 lakh crore to Rs 5.62 lakh crore as of Oct ‘18 from Rs 3.61 lakh crore in the same period of last year. This is the largest credit growth witnessed by any of the sector in the economy during the last 12 months.

The following chart shows the increasing credit share % of Gross Bank Credit to NBFC.

However, bank credit to NBFCs slowed down to 13.3 per cent during the April to October period of 2018. When the IL&FS payment crisis hit the financial sector in August, bank credit to NBFCs slowed down considerably, leading to a liquidity squeeze. Banks significantly reduced their funding to NBFCs, virtually closing a major resource funnel for NBFCs and housing finance companies. The fundamental issue, however, is an asset-liability mismatch in the operations of NBFCs like IL&FS. To explain in short as an example, these firms borrow funds — say for three or five years — from the market and lend for longer tenures — 10 to 15 years. In a rising interest rate scenario, this contracts the margin considerably and sourcing of funds becomes tough, thus hurting the NBFCs.

Credit to Personal Loans

At about Rs. 20.4 lakh crores, credit to personal loans has sustained a growth of 16% y-o-y as of Oct ‘18. Housing loans, contributing to more than 50% of personal loans, has seen its segment grow at 17.6% since last year.

Major reasons supporting its growth are:

- With high NPAs in other sectors, banks find it easier to give home loans with low margins and low defaults

- Growing affordability for the first-time home buyers, supported by government incentives like the PM’s Awas Yojana has resulted in a rise in primary home purchases, especially in the affordable housing segment.

Government and the RBI

The Government and RBI has been at odds over the past few months. While the RBI has asserted that the bank lending is growing at a brisk pace, the government and the industry lobbies insist that the credit taps have remained shut. The data does back the fact that even when all sectors have seen an inflow of credit, few of the sectors took the major share of the loans during the year.

For instance, for every ₹100 of new bank loans added, it was services which bagged ₹50, while industry received just ₹10. Out of the ₹10 advanced to industry, large firms gobbled ₹8.30, while medium and small enterprises were left with just ₹1.70. As much as ₹31 out of every ₹100 of new bank loans did not go to businesses at all, but to retail folk borrowing towards their home, credit card or personal loans.

Although the credit flow to services appeared plentiful, NBFCs (financial services) cornered a disproportionate share of loans to this sector. With as much as ₹21 of every ₹50 in new bank loans to services went into NBFCs, direct borrowers in services were left with smaller slices of the loan pie. NBFCs in turn seem to have funnelled this money into consumer loans, real estate, affordable housing, loans against property and shares, promoter funding and infrastructure.

There has been concern about a squeeze on bank credit to MSMEs post-demonetisation. Overall loans to MSMEs doubled this year, with ₹11.6 out of every ₹100 in new bank credit flowing to them. But the MSMEs in services hogged ₹11 of this, leaving manufacturing MSMEs with just ₹0.60. The surge in services MSME loans likely reflects small-ticket loans to entrepreneurs under the Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana, which has seen a big push by the government.

Within the priority sector, though services MSMEs, agriculture and housing saw brisk growth, exporters were starved of credit, with their credit flow in negative territory for the last three years. Agriculture, bagging ₹8 of every ₹100 in bank loans has also seen a dip in credit flow compared to the pre-demonetisation period.

At this station, it is important for the Centre and the RBI to let banks to make their own decisions on allocating credit, instead of funneling it to specific segments. For banks to regain their appetite to lend to riskier borrowers, they must first digest the mountain of bad loans that today account for over 11% of their loan books.

References:

- https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/stocks/news/learn-with-etmarkets-how-does-food-credit-work/articleshow/51888321.cms

- https://rbi.org.in/Scripts/Data_Sectoral_Deployment.aspx

- https://www.indiamacroadvisors.com/page/category/economic-indicators/money-and-banking/bank-credit-nonfood/

- https://indianexpress.com/article/business/banking-and-finance/reserve-bank-of-india-credit-nbfc-5473509/

- https://www.thehindu.com/business/bank-credit-is-it-growing-and-wheres-it-going/article25758721.ece

- https://indianexpress.com/article/business/banking-and-finance/reserve-bank-of-india-credit-nbfc-5473509/

- https://www.livemint.com/Opinion/KbpiYyFXCs1Y99lEydzrCL/The-tale-told-by-the-bank-loan-numbers.html

Disclaimer – All the views expressed are opinions of Networth – IIMB Finance Club – members. Networth declines any responsibility for eventual losses you may incur implementing all or part of the ideas contained on this website.

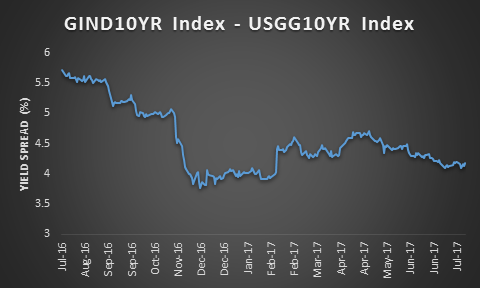

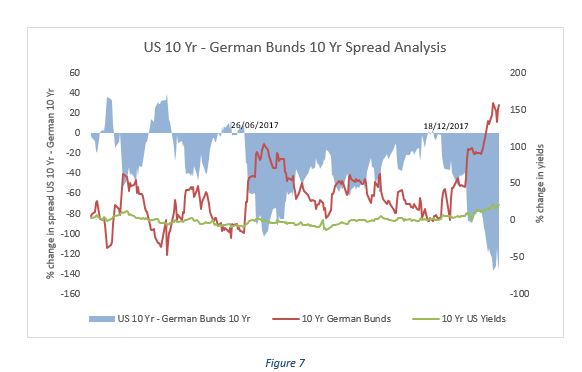

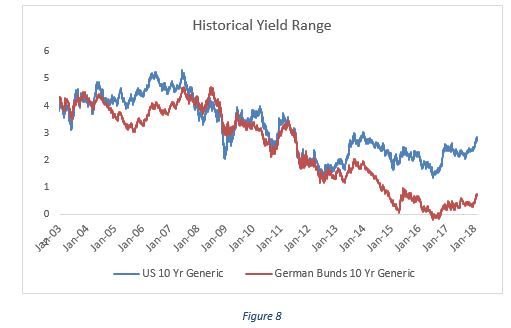

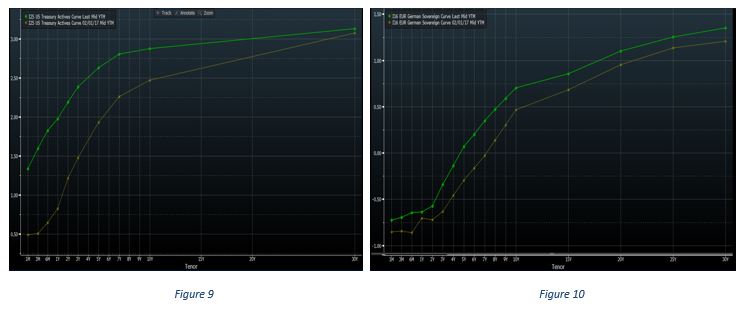

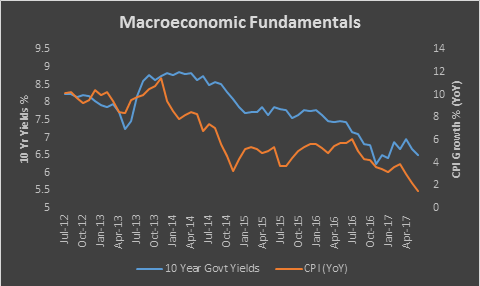

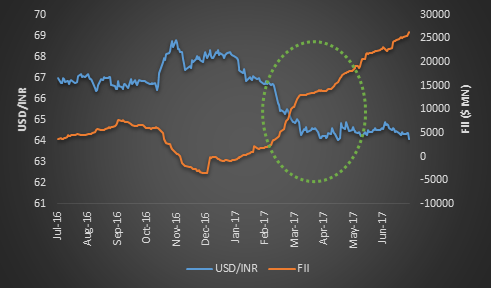

Despite the rate hike cycle in US resulting in a decrease in the interest rate differential in 10 year government yields between India and US, there has been minimal impact on the capital inflows in India. This shows that a rate cut by 25 bps at this point of time will not hurt the capital inflows given the optimism in investor sentiment owing to India’s growth story.

Despite the rate hike cycle in US resulting in a decrease in the interest rate differential in 10 year government yields between India and US, there has been minimal impact on the capital inflows in India. This shows that a rate cut by 25 bps at this point of time will not hurt the capital inflows given the optimism in investor sentiment owing to India’s growth story.