Blog by: Ayush Agrawal (PGP 2016-18)

As we discussed in part one, a loan becomes Non-Performing Loan (NPA) when any form of repayment (principal or interest) is due for more than 90 days. Based on the number of days past due date, the RBI guidelines mandate banks to classify them as sub-standard assets, doubtful assets or loss assets with different provisioning norms. Moreover, any non-performing loan can trigger IBC (Insolvency & Bankruptcy Code, 2016) proceedings against the debtor (the company that has taken the loan) by filing a case in NCLT (National Company Law Tribunal).

NCLT is the adjudicating body for all disputes related to companies. Cases filed under IBC also come under the gamut of NCLT. However, NCLT is not the only adjudicating body in the IBC process, and we will allude to other bodies involved later. As per IBC, the case against a debtor can be filed by several entities which are listed below:

- Financial Creditors: A financial creditor is someone to whom a financial debt is owed. Financial debt refers to interest-bearing debt including any type of term loan, bond or debenture issued by the company etc.

- Operational Creditors: An operational creditor is someone to whom an operational debt is owed. Operational debt refers to claims in respect of provisions for goods or services including dues payable to Central Government or State Government.

- Corporate Applicant: The corporate debtor himself can also file a case in NCLT for insolvency/bankruptcy.

Once the case has been filed by either of these three entities, NCLT needs to identify whether a default has occurred within a period of 14 days (extendable up to 21 days) based on the corresponding documents provided by the applicant and admit the case. If a financial creditor has filed the case, it needs to recommend the appointment of an Interim Resolution Professional (IRP) – which is not necessary if an operational creditor/corporate applicant has filed the case. An IRP is a certified professional (check link for details) who is responsible for running the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) once the case has been admitted.

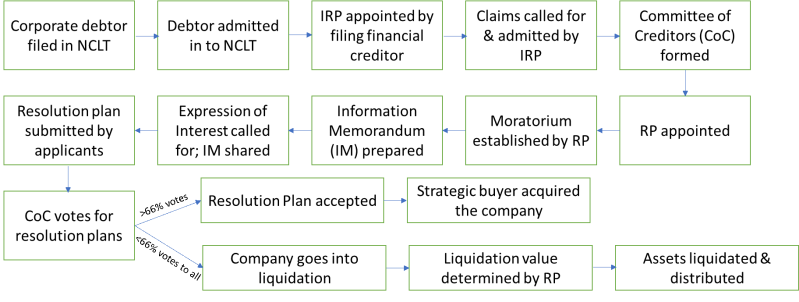

Let us look at how does the CIRP process works. After the case has been admitted into NCLT, a moratorium prohibiting continuation of existing suits/filing of any further suits on the company (corporate debtor) is declared by the IRP. The IRP simultaneously issues a public notice calling for claims on the company by financial and operational creditors (All financial creditors need to file claims within the stipulated period if they wish to be part of the CoC). The claims are admitted by the IRP after a careful analysis of supporting documents provided by creditors. Based on the admitted claims, a Committee of Creditors (CoC) is formed where only financial creditors have representation with a voting share in proportion to the financial debt owed to them. (Note: It is not necessary for operational creditors to file their claims within the deadline) The CoC then appoints the Resolution Professional (RP) which can be the same as the IRP or a replacement.

The RP is responsible for conducting the CIRP process further. The RP prepares an Information Memorandum (IM) which includes all relevant information about the debtor that may be required for formulating a resolution plan. A resolution plan details how the company would be restructured so that it operates as a going concern in future and is able to generate sufficient cash flows to service the debt. The RP calls for Expression of Interest (EoI) for submission of resolution plans. Resolution applicants are mostly strategic buyers who are either industry leaders or conglomerate houses that have the ability and willingness to cure the corporate debtor in default. The resolution applicants perform their own analysis of the company (corporate debtor) based on the IM provided, amongst other sources, and determine if there exists value in the company as a going concern. Based on the analysis, they submit resolution plans to the RP which are opened in a CoC meeting. The CoC is required to vote on each resolution plan. The voting generally happens of the basis of which plan will yield highest recovery to financial creditors. A minimum of 66% CoC voting share is required for any resolution plan to get accepted in CoC. Once a resolution plan is accepted by the CoC, it is binding on the corporate debtor and its employees. The IBC also mentions that in such a case, the dissenting financial creditors (those who did not vote in favour of the resolution plan) and all operational creditors will be paid at least the liquidation value (the concept of liquidation value is discussed below) in priority to the assenting financial creditors.

Figure 1: CIRP Process

The entire CIRP process needs to be completed within 180 days, extendable to 270 days. If the CoC and RP fail to accept any resolution plan within this time frame, the company goes into liquidation. For determining the liquidation value of the company, the RP appoints three liquidation professionals to independently determine the liquidation value of the company. An average of the two closest liquidation values is taken as the liquidation value of the company by the RP. For Eg. If the valuations by three liquidators come out to be INR 3000 Cr, INR 3300 Cr and INR 3350 Cr, then the liquidation value as taken by the IRP would be equal to INR 3325 Cr.

If the company goes into liquidation, the recovery to all creditors (financial and operational) as well the workmen and employees is based on the liquidation waterfall that has been defined in IBC. As per the liquidation waterfall, the distribution of liquidation value is to be done in the following order:

- CIRP costs (costs incurred during the CIRP process including RP fees) and liquidation cost

- Workmen dues for the period of last 24 months preceding liquidation process commencement date and secured creditor dues given that the secured creditor has relinquished the charge on his security. This essentially means that the creditor would no longer have a lien on the asset which was kept as security against the loan.

- Employee dues for the period of 12 months preceding liquidation process commencement date

- Debt owed to unsecured creditors

- Central government/State government dues

- Preference shareholder

- Common equity holders

Now that we are clear on how the IBC process works, let us look at the other bodies apart from NCLT which help in the adjudication of the process. National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) and Supreme Court (SC) are two adjudicating bodies which seek to address the grievances of any entity associated with the CIRP process. If any participant in the process feels that injustice is being done based on the IBC law, then he/she can approach NCLAT and ultimately the Supreme Court to seek justice. As soon as any entity approaches either NCLAT or SC for grievance redressal, the NCLT process automatically comes to stay.

Post the release of the first draft of IBC there have been several amendments in a short span of time. This has kept both foreign and domestic investors guessing, and several are now shaky about investing in distressed assets in India. Some of the major amendments made in IBC along with their implications are:

- Home buyers as financial creditors: The home buyers did not have any say in CoC based on the original code. However, Jaypee Infratech is a case in point (2017) which highlights the importance of including home buyers as financial creditors in case of real estate debtors. Since the real estate projects are financed by home buyer money, they are the rightful financial creditors in the IBC process. (Some people say that including home buyers as financial creditors has negative implications. The jury is still out, and interested people might want to read up on it)

- Exclusion of related parties from submitting a resolution plan: This has thus far been the most significant amendment in IBC. Listed under section 29A, this amendment prohibits any party related to the existing promoter in any way as well as any party which had defaulted on any of its related party (associates/subsidiaries) debt at the time the corporate debtor in question went into NCLT, to participate in the CIRP process as a resolution applicant. The objective of this section was to prevent malicious attempts to acquire the company and give it back to the original promoters. However, the fine prints in this section are so stringent that they make almost every big conglomerate house in India ineligible to participate in the resolution process. (Interested people can read about the case in point of Essar Steel)

- The omission of dissenting financial creditors from IBC: The latest amendment which came about last week has excluded the concept of dissenting financial creditor. This means that, while earlier dissenting financial creditors were paid liquidation value in priority to the assenting financial creditors, now they will no longer enjoy such a privilege and the accepted resolution plan will be binding on all financial creditors. This is a progressive step in a way that it encourages financial creditors to accept reasonable resolution plans even though the recovery might be lesser than the liquidation value.

We hope that students who have read the first two parts of this blog post are now comfortable with what the IBC as a law and CIRP process is all about (the fact that you guys made it past IBC and CIRP abbreviations in this sentence suggests that we have been successful in our attempt). Today, the entire country is reeling under the weight of distressed assets, and there is a lot of pressure on the government to resolve them. As per our prediction, there is still a lot of contagion effect which has not yet been realised and hence the exciting times in distressed asset investing are here to stay. Not only does it open several new opportunities in the world of finance, but it also gives one the satisfaction that the malaise which the country was going through is finally being cured (trying to find the philosophical us somewhere behind the opportunistic capitalist).

Disclaimer – All the views expressed are opinions of Networth – IIMB Finance Club – members. Networth declines any responsibility for eventual losses you may incur implementing all or part of the ideas contained on this website.