Germany, the largest Eurozone economy, has so far failed to distinguish itself from its regional peers as far as economic growth is considered. The country clocked 0.1% GDP growth in the third quarter thus marginally saving itself from the ignominy of recession (had registered a sub-zero growth in the previous quarter). The underlying cause for such a performance however is very different from those of its peers.

Germany is one such nation that has a long running current account surplus – its national savings exceed the national expenditure by more than 6 per cent of the GDP. This can be attributed to the general tendency of the Germans to amass wealth. Also, the economy doesn’t produce sufficient assets/avenues for investment. As a result, a major chunk of the investment goes to its neighbours and emerging markets around the world, who are willing to sell their assets to the German savers. This, however, also generates a huge uncertainty for the German economy. Though their desire to invest in the foreign assets is unlimited, the tendency of the other countries to borrow and issue debt assets is not.

This is exactly the reason for the current state of the German economy. Though the Germans continue to save a high portion of their income, the peripheral countries do not wish to borrow as their external debt has surpassed 100 per cent of their GDP and has become unsustainable. The Germany then turned to the emerging markets for rescue. However, with the recent slowdown in China, Russia and also several Gulf countries, the situation has resulted in an excess of savings leading to slow GDP growth and possibility of deflation.

In such a situation, there might be two broad ways in which the Germans could beef up their economy. The first one is to produce more of own assets and incentivize people to invest in them. This, it may accomplish by providing more tax incentives to different businesses to encourage private investment. It may also pare down VAT to further promote household spending, which has shown marginal improvement in the previous quarter and thus needs to be sustained.

The second and perhaps not so obvious solution might be introduction of another “Marshall plan”. The prime difference though being, that this time, Germany would be at the offering rather than at the receiving end. The Economic Cooperation Act- 1948 popularly known as the Marshall plan was carried out by the US under which it helped revive several European economies post the World War II. Though it also aimed at restoring economic and political stability in Europe through checking the growth of communism, it primarily allowed US to recover from the economic slump in 1946-47 and enter a period of economic boom.

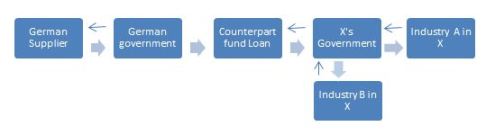

Marshall plan works by way of providing a beneficiary nation, say X, with financial aids in form of grants and loans together referred to as the Counterpart funds. X may preferably be an current/prospective importer for Germany which would additionally help provide an extended market for the German exporters. The loans thus provided under this plan are recycled into different businesses over several years and the compounded amount paid back to the lender country (Germany) resulting in a substantial increase over the principal value. Fig 1 is an illustration of how the recycling mechanism would lead to increase in the loan capital.

A supplier/exporter in Germany would provide his goods for shipment & paid by the German government and this amount is then credited towards the counterpart fund loan. The goods would be shipped thereafter to X where the party overlooking the allotment of the Counterpart funds exchanges them with X’s government and subsequently the importing industry (say A) for the corresponding amount in X’s currency, usually on credit (Note that this doesn’t require Government of X to maintain any German foreign exchange reserve). The credit, along with the interest amount, when paid off by A to the Government of X, would not paid back to Germany but thereafter used to fund more industries (B in figure 1). This cycle thus leads to compounding of the original sum over several years, through reinvestment of principal & the interest thus obtained, in different industries.

Fig 1. Marshall Plan with Germany as the financier

A key aspect that needs to be highlighted here is that the funds thus invested are not in the fixed income/debt securities of X, but in the working capital of its industries. This model is not only more sustainable because the X’s government original debt is not increased each time an industry is funded, but is also more profitable as the returns received are much higher vis-à-vis those received from Germany investing in the sovereign government bonds of X.

Prospective candidates for X– Marshall plan acts to provide an increase of the beneficiary’s economy by way of promoting its industries through easier availability of raw materials as well as the businesses through availability of overseas investments. The major prospective takers for such a Marshall plan would thus be economies currently struggling in absence of sufficient capital or raw materials to feed their industries. Also as discussed earlier, an existing importer nation or one that is a prospective buyer for the different German exports would be an ideal candidate for a beneficiary for Germany, as this would provide it with two-pronged way to promote its economy- through providing an attractive investment avenue for its savers and also through providing a new/bigger market for its exporters thus providing them incentives to increase private investment.

Both these factors enable us to come up with the following two most likely candidates: Greece and Spain. The former suffers from a severe lack of capital available for starting/sustaining new businesses as well as high cost for raw materials for its infrastructure & energy projects due to austerity measures, making it one of the worst performing economies in the recent time. Similar is the case with Spain where low investor confidence has led to frustratingly slow growth over past several years. Additionally, these two also happen to be major German import partners making them ideal beneficiaries for a German Marshall plan.

Besides the above stated tangible benefits from a Marshall plan, it would help Germany build networks and trade links that could continue to exist far beyond the duration of the plan. It might also allow Germany influence some of the protectionist policies in these European nations, allowing it to promote further trade & contribute to uplifting of economy of the EU. Finally it might serve to market German economy as one that is cooperative and visionary, which would prove beneficial for its other trade relations in the longer run.